A violin is made of wood and glue, along with a few extra components like metal or synthetic material that is often used for the strings.

Imagine that these instruments—that a luthier who makes and repairs stringed instruments takes such care and skill in crafting—simply boil down to wood, glue, metal, and possibly some synthetic components.

Most modern-day violins are manufactured using techniques grounded in practicality for the purpose at hand. Yet, all strive to maintain some level of traditional artistic craftsmanship while still delivering that quality sound we come to expect from the instrument.

A luthier’s craftsmanship when making of a violin—with its unique shape or figure—involves two main goals:

- Create a musical instrument that produces the quality sound of music

- Create a work of art that mimics the efforts of violin makers from the 17th century who set the tone for how the instrument should look and feel

Let’s examine the basic parts of a violin, from the most expensive models all the way down to the cheapest. The primary difference lies in the materials used, which ultimately affect sound quality. Other disparities involve the finishing touches the violin maker adds as their signature touch.

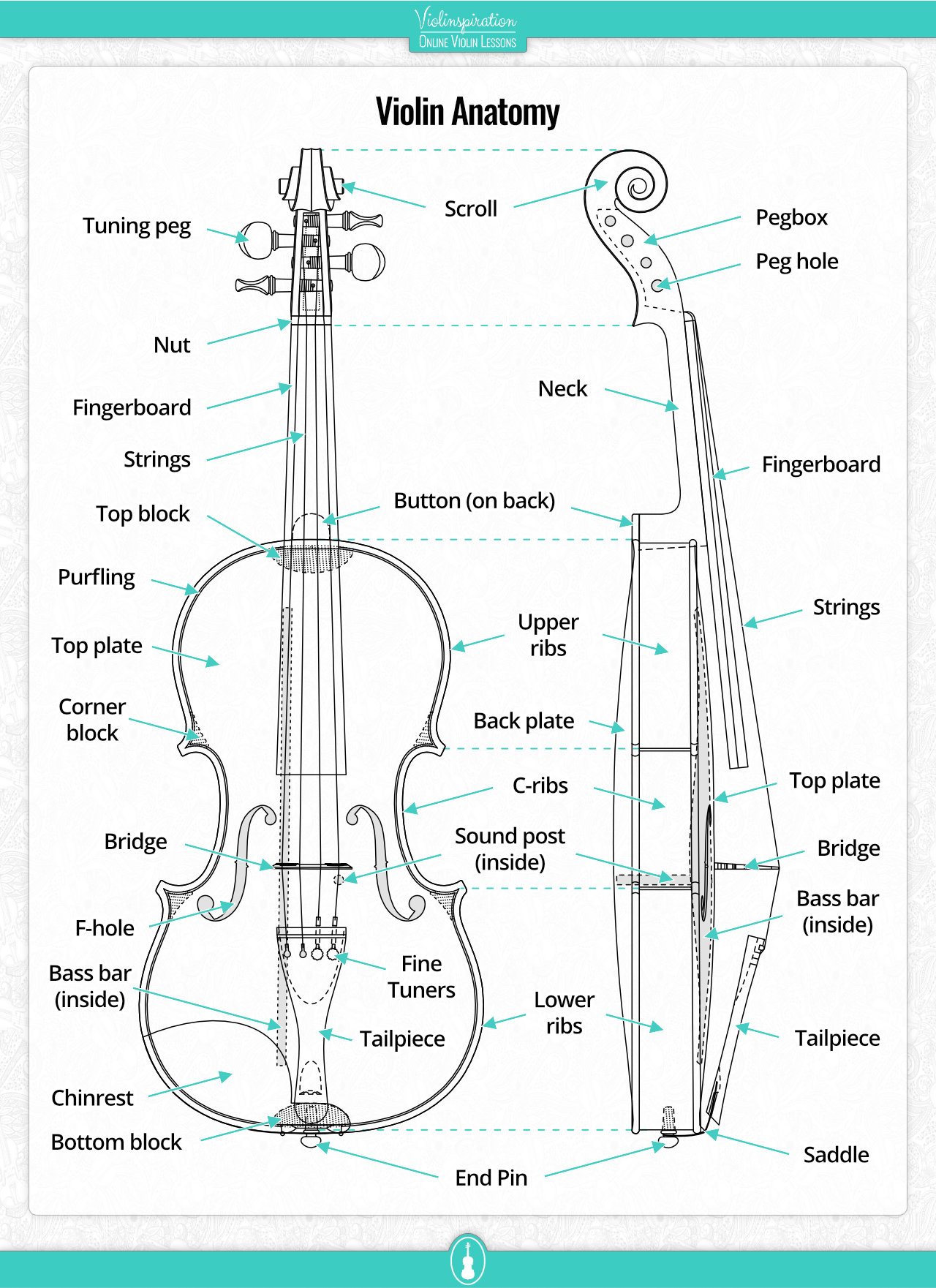

Violin Anatomy

Set of 3 Posters

Parts of the Violin and What They Are Made Of

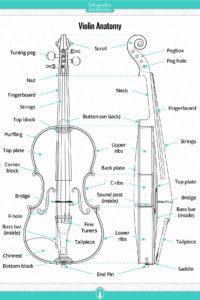

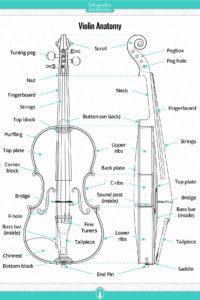

Like any string instrument, a violin consists of a few basic parts that include the body, the fingerboard, tuning pegs, and strings. Working together, they all create the classic sound and look we have come to recognize. A skilled luthier understands the importance of each part and makes each one with care.

After a luthier lovingly crafts an instrument, the player is the one who will produce music from the piece using a bow: a key accessory typically made of wood and horsehair (between 160 and 180 individual hairs, to be exact). Check out my detailed post to learn more about the bow, many of which are currently made using synthetic materials such as fiberglass or carbon fiber.

Now, let’s dive into some details with respect to the external and internal parts of the violin.

External Parts

Body of the Violin

Let’s start with the body. If we go back to the instrument’s roots and get fancy with Latin terms, we would call this the corpus. The body consists of the top of the violin, the back or bottom, and the ribs, which are the sides.

Ever wondered how a violin body looks without all the other elements added in? Check it out here:

A mainstay in modern violin styling is that most bodies are constructed with wood. Sounds simple enough, right? Yes, but remember that the wood must be dense, fairly easy to shave yet not too soft, and stored at a specific humidity.

Many violin makers prefer spruce and maple, which are both known as great sound conductors.

Do you know why the holes on top are called “f-holes”? It’s simple! They reflect the shape of a fancy lower-case “f”. These are also common features of a viola, cello, and double bass.

Since the f-holes must be carved from the top of the instrument, spruce is often the wood of choice here. It is strong, yet flexible and light at the same time. On the other hand, maple is commonly used for the bottom and the ribs, offering a beautiful wood grain look that adds to the artistic quality of the craftsmanship.

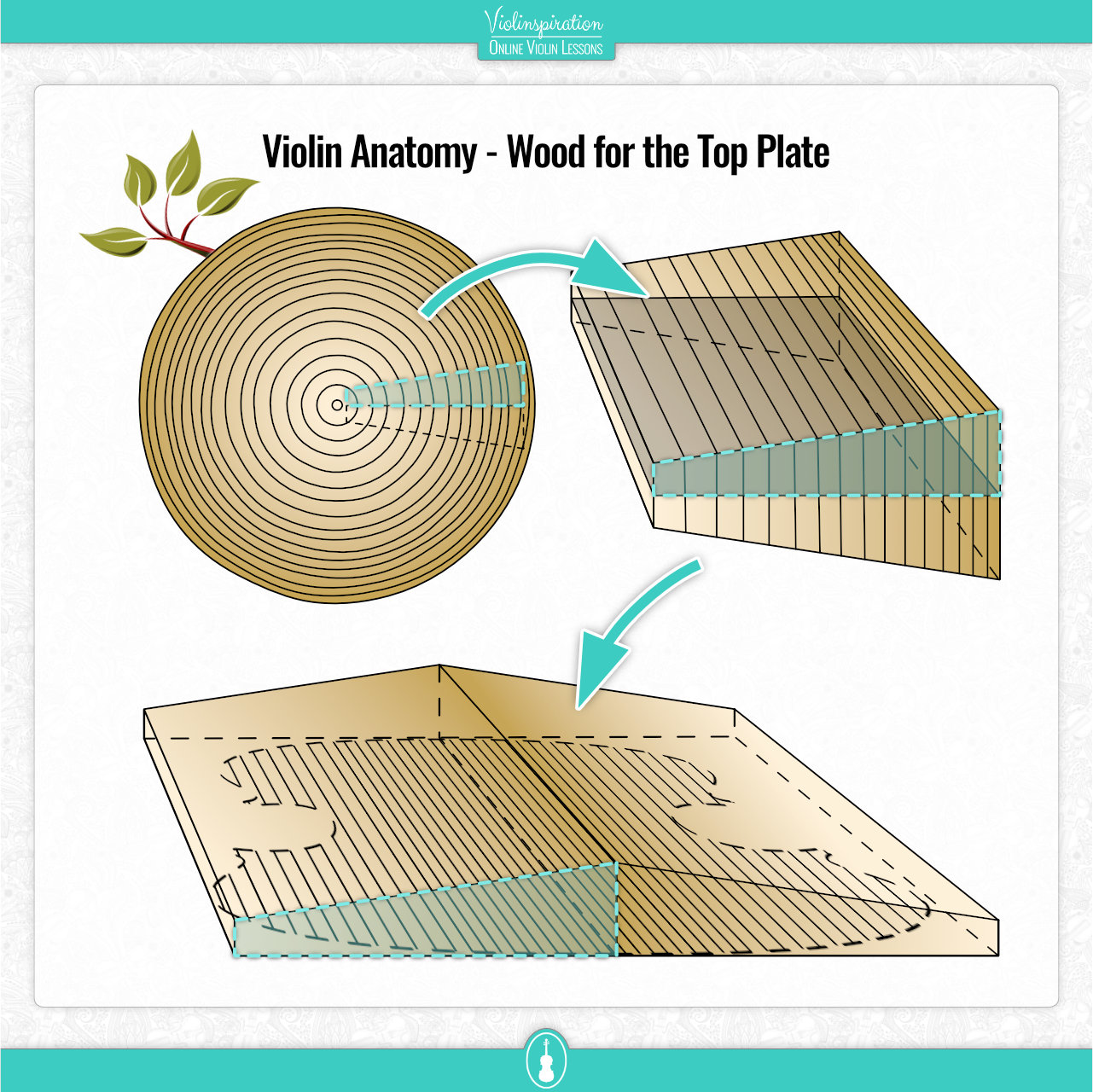

Choice and treatment of the wood

Regardless of the species, the wood used for violin making requires special treatment. Strong pieces with straight-running fibers are preferred. Sometimes, a hatchet is used to split a block of spruce wood so as to not break the fibers up.

In well-crafted instruments, the block of wood used is carefully selected and prepared. When spruce is cut directly from a tree, it is crafted in a special way. Specifically, the outer part of the age rings is thicker and thereby employed for the top piece of the instrument where the bridge rests. This process also adds to the sound vibration quality that follows a symmetrical grain of wood.

Ribs

The ribs, or sides, of the violin give the instrument depth. This wood needs to be strong, dense, and an excellent sound conductor. Many luthiers use maple or spruce for this part of the instrument.

In the video below—recorded by one of my Julia’s Violin Academy students, Jerry Everard—you can observe how a rib is bent. Jerry is also the man behind the violin parts sprinkled throughout this article.

Purfling

Ever wonder what the purpose is of that decorative inlay of black and white that adorns the edge of the violin? With a function that goes beyond just looking good, the purfling helps to reduce cracking on the top and back of the instrument.

The purfling is made out of three pieces of wood that are sandwiched together. It is then glued into a small channel cut along the edge, all the way around the instrument.

Pearwood or poplar wood (that has been dyed black) works well here, as does maple. While ebony is black by nature, it is brittle and difficult to bend without breaking. Throughout history, some creative violin makers have utilized some unusual materials to create the purfling such as corn husks, paper, and whale baleen.

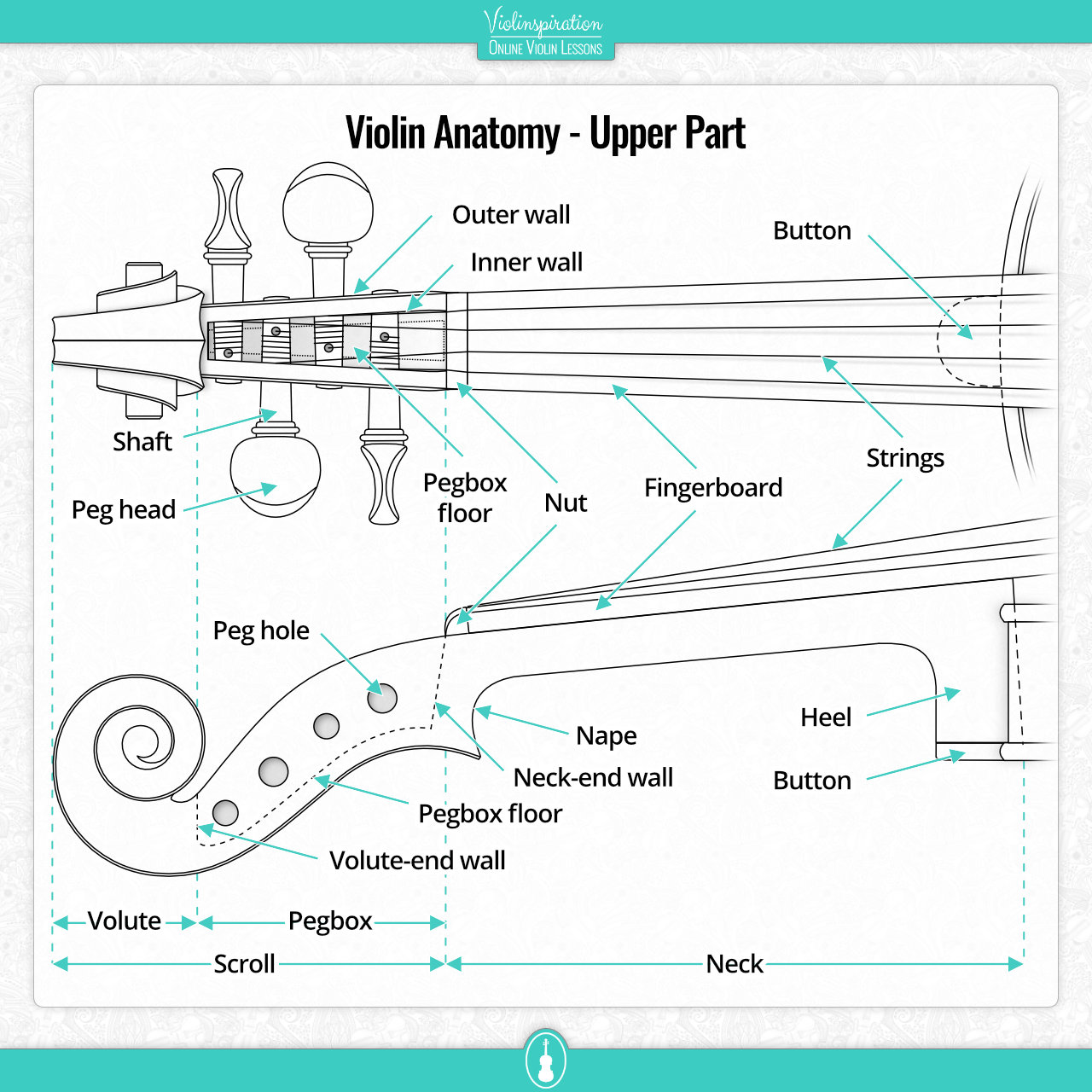

Scroll

What do you usually think of first—besides the f-holes—when you picture a violin? It’s probably the scroll. One article that makes a violin unique, the scroll is a beautiful decorative curved piece at the top of the instrument that resembles a spiral. Creative versions also exist, like the sculptured head of a human or an animal. Usually, violin makers carve this piece out of the same wood used for the pegbox—typically maple or poplar.

Tuning Pegs

The tuning pegs do exactly what their name implies: tune! Strings wrap around the pegs so that the player can tighten them for a higher pitch or loosen them for a lower tone before they play. If you turn the pegs too far, the string will break. If they are not turned enough, the instrument will be out of tune and/or boast loose strings that are not even playable. Check out my article about tuning with pegs to gain additional familiarity with this aspect of playing.

The pegs must be cut out of durable wood that is equipped to withstand tension in the strings as they are tuned, such as:

- ebony

- rosewood

- boxwood

Sometimes, this part of the instrument is cut from the same block of wood as the scroll.

Pegbox

The pegbox is a portion of the scroll that is hollowed out to allow for insertion of the tuning pegs. The opening is located just below the decorative part on top of the instrument (the scroll). The pegbox not only holds the pegs in place but also accommodates the ability to turn them when tightening or loosening the strings.

Nut

The nut, or sometimes a string nut, is located at the top end of the fingerboard and directs the strings down the fingerboard until they reach the tailpiece. Four small notches, or grooves, are carved into the top of the nut where the strings will be placed before they are wound around the tuning pegs. The nut adds height to the strings so that they touch the fingerboard only when pressed by the player.

The nut is usually made out of ebony, ivory, cow bone, or brass. Sometimes, however, plastic or an acrylic polymer mix called Corian is used instead.

Neck

Extending from the body of the violin up toward the scroll, the violin neck is typically made out of maple. It is the portion of the instrument that holds the fingerboard and strings, ending at the top and pegbox.

The neck is a crucial component that must be strong for the strings and tension they create. If it is warped or improperly glued to the saddle and body, the sound will suffer accordingly.

This picture depicts what the neck, pegbox, and scroll look like when carved from one piece of wood:

Violin Strings

When a musician picks up the bow and plays, the violin strings vibrate and then transfer this vibration to the body of the violin where it is amplified and resonates.

While the quality of the bow impacts how the instrument sounds, strings are also needed to make music. Without the strings, the violin is nothing more than a beautiful wooden sculpture.

Violins typically boast four strings (see examples of instruments with more strings here), which are usually tuned to G, D, A, and E—with G as the low pitch.

Beyond this, there are three major types of strings:

- Gut: traditional, classic sound that requires frequent tuning

- Steel: stays tuned and is less susceptible to humidity and other weather conditions

- Synthetic nylon: a great combination of warm tones with the stability of steel

Core and Winding

In the past, the core of the violin strings was constructed using “catgut”: twisted sheep’s intestines. So don’t worry—no cats were harmed in the process! The name—derived from the term “kitgut,” meaning “kitstring”—refers to the string used when making a kit or fiddle.

Nowadays, three types of cores are used: gut, steel, and synthetic polymers (e.g., nylon).

Strings are always wound over the peg. If they become pinched or wind over each other, they can become damaged and break more easily. Consequently, catgut core strings were always wound with metals like copper or silver. Now, additional types of metal are used including gold, bronze, steel, aluminum, tungsten, titanium.

Click here to learn more about strings and what to consider when looking for a new set.

Bridge

The bridge is the carved piece of wood that lifts the strings up from the top of the violin. Here are some fun facts about a violin bridge:

- It is not symmetrical.

- It is usually made of maple.

- It allows each string to freely vibrate while transferring these vibrations to the inside cavity of the body.

The location of the bridge and the method used to carve it have a huge impact on tone and affect the ease (or difficulty) of playability. Hence:

- It should be straight and parallel to the fingerboard.

- It should be centered between the f-holes.

- Its feet must lay flat against the belly.

Can you spot the three rules applied to the instrument pictured below?

Fine Tuners

Just what are those little screws?

To allow the violin player to precisely tune the strings, small screws are either attached to or built into the tailpiece. These fine tuners can be either installed or removed and can occupy all strings; yet, they are usually on the A and E strings—or only on E. The reason why? It’s much easier to tune lower frequency strings using only tuning pegs than it is to tune higher strings in the same fashion.

Tailpiece

The tailpiece serves as the “anchor” that holds the strings to the body of the violin and often includes fine tuners. The strings wind around the pegs at the top, run down along the top of the neck, and then are held in place at the bottom with the tailpiece.

The tailpiece can be made from:

- Ebony

- Rosewood

- Boxwood

- Pernambuco wood

- Dark Paper (compressed paper and resin)

- Plastic

Check out a tailpiece with a set of fine tuners in the picture below:

The end button on the violin holds the tailpiece firmly in place using the tailgut.

Traditionally, the end button is made out of ebony. However, any type of wood can be used, or perhaps even metal—like titanium.

Chinrest

So, just what is your chin resting on while you play a violin?

Violin chinrests may be made out of a variety of materials, including:

- Boxwood

- Rosewood

- Ebony

- Composite materials

- Sonowood (most recently)

Non-wood options are hypoallergenic: perfect for musicians with sensitive skin or for those who are allergic to some kinds of wood or metal brackets. The brackets are designed to clamp onto the ribs and hold the chinrest in place. To learn more about this topic, check out my post about chinrests.

Saddle

Did you know that all it takes to relieve pressure from the body of the violin is a small rectangular block of wood? This is called the saddle.

Specifically, this component sets out to relieve pressure caused by string tension. It is usually made out of ebony and placed under or near the chinrest.

In the picture below, you can observe how the tailgut—located under the chinrest—holds the tailpiece and winds around the end button while pressing against the saddle.

Internal Parts

The external parts of a violin may command all the attention, but internal features are very important as well. Inside the violin, some crucial pieces are never even seen by the player: including a bass bar, blocks, and a soundpost.

Soundpost

The soundpost is made out of the same wood that is used on the top piece: usually spruce.

Craftsmen who make these pieces know that the soundpost gives support to the treble side: which contains the A and E strings (see poster). If it is missing or poorly constructed, the entire top of the instrument would cave in. Moreover, vibrations would not transmit in the way they should, resulting in a much different sound (not full). Perhaps this is the reason why the soundpost is referred to as “the soul” in different languages.

Bass Bar

Did you know that inadequacies in one little piece inside the violin could negatively impact the instrument’s entire sound?

The bass bar is a piece of wood located below the strings on the underside of the faceplate. It is a crucial component that allows lower pitches to resonate when the strings are played with the bow, and hence, a very important piece that must fit perfectly.

You can check out how this looks in the picture below:

Blocks Inside the Violin

No part of a violin is insignificant! The bottom part of the instrument’s neck is called the heel, which connects to the interior top block (a piece of wood on the inside of the violin). The heel is usually made from spruce or willow, and the neck block is sometimes called the “top” or “upper” block. Additionally, the inside of the violin features corner blocks, and there is a lower block on the inside as well.

Take a closer look at them in the picture featured below:

Final Note

Even though the violin is one of the world’s most beautiful instruments, it is constructed using fairly simple materials. As such, its beautiful sound lies not in any special building blocks, but in the craftsmanship of a luthier in the hands of the player.

I hope this article gave you some new insight into what your violin is made of!

Feel free to download all violin anatomy posters here:

Violin Anatomy

Set of 3 Posters

Last but not least, I’d like to extend a GIANT THANK YOU to Jerry Everard—a student of mine at Julia’s Violin Academy—for sharing his photos and allowing me to use them in my blog posts.